Brazil, a nation of continental dimensions, boasts one of the cleanest and most renewable-heavy energy matrices in the world, dominated by vast hydroelectric power. It is a country that has successfully electrified nearly every corner of its territory, with official statistics showing that over 99% of households have access to electricity [1]. This achievement, a testament to decades of ambitious infrastructure projects, paints a picture of progress and modernity. Yet, beneath this surface of near-universal access lies a stark and painful paradox: for millions of Brazilians, particularly the poorest, electricity is not a readily available commodity that empowers their lives, but a luxury that consumes a crippling portion of their monthly income. The light switch, a symbol of modern convenience for many, is a source of constant financial anxiety and impossible choices for the most vulnerable.

This is the reality of **energy poverty** in Brazil. It is a silent, insidious crisis that extends far beyond the simple presence of a power line. It is a crisis of affordability, where the cost of keeping the lights on, refrigerating food, and powering the most basic of appliances forces families to make agonizing decisions between energy and other essential needs like food, medicine, and education. A recent, groundbreaking study by the Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet (GEAPP) and PSR found that for Brazil’s most vulnerable citizens, electricity bills can devour up to **18% of their monthly income**, a figure equivalent to nearly a quarter (23%) of the cost of a basic food basket [2]. This is not merely a statistic; it is a daily struggle for survival and dignity played out in millions of households, from the dense, labyrinthine favelas of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro to the isolated rural communities of the Amazon rainforest.

How can a country so rich in energy resources have electricity that is so prohibitively expensive for its most vulnerable citizens? The answer is not a single, simple cause but a complex and deeply entrenched web of structural inefficiencies, regressive taxation, convoluted subsidies, and systemic inequities that have been woven into the fabric of the Brazilian electricity sector over decades. The monthly electricity bill, the *conta de luz*, is far more than a charge for energy consumed; it is a ledger of sector-wide costs, poorly targeted social programs, and government taxes that are disproportionately borne by those least able to pay. It is a reflection of a system that has, for too long, prioritized industrial development and the financial health of its operators over the basic needs of its people.

This in-depth article will deconstruct the Brazilian electricity bill to uncover why it weighs so heavily on the poor. We will explore the intricate components of the tariff structure, from generation costs and the controversial tariff flag system to the labyrinth of taxes and sector charges that inflate the final price. We will examine the government’s primary response, the Social Electricity Tariff (Tarifa Social), and analyze its historical shortcomings and recent, ambitious reforms under the new “Luz do Povo” program. Furthermore, we will delve into the systemic issues of energy theft, the complex role of privatization, and the profound impacts of energy poverty on health, education, and social mobility. By dissecting this complex issue, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of one of Brazil’s most pressing social challenges and explore the proposed pathways toward a more just and equitable energy future for all Brazilians.

The Paradox: Brazil’s Green Matrix and High-Cost Reality

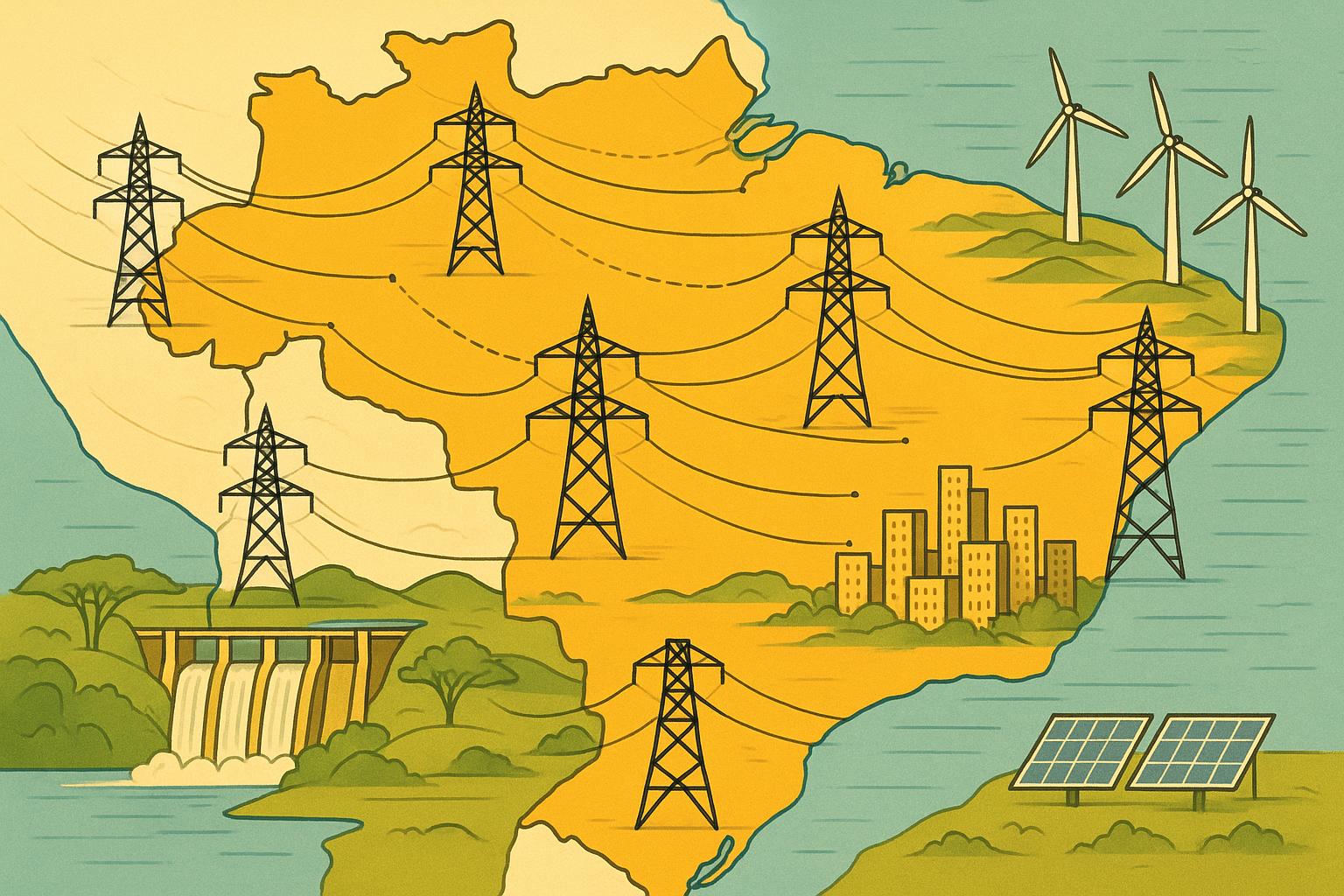

To understand the high cost of electricity in Brazil, one must first appreciate the paradox at the heart of its energy system. Brazil is rightfully lauded as a global leader in renewable energy. Its electricity matrix is dominated by hydroelectric power, which typically accounts for over 60% of the country’s total generation capacity. This massive reliance on water resources, supplemented by a growing portfolio of wind, solar, and biomass, gives Brazil one of the cleanest energy profiles among major world economies. In theory, this abundance of renewable resources should translate into cheap, affordable electricity. However, the reality on the ground is starkly different, a consequence of historical development choices, geographical challenges, and climate vulnerability.

The heavy dependence on hydroelectricity, while a blessing for the environment, has become a source of significant price volatility and risk. Brazil’s climate is susceptible to periodic droughts, which have become more frequent and severe due to climate change. When reservoir levels drop, the country is forced to activate its network of thermal power plants, which run on more expensive and polluting fossil fuels like natural gas and diesel. This switch from cheap hydro to expensive thermal power has a direct and immediate impact on electricity prices for all consumers. This is where the controversial **Tariff Flag System** comes into play, a mechanism designed to pass these extra generation costs directly onto consumer bills in real-time, creating a system of unpredictable and often punishing price hikes.

Furthermore, the vastness of Brazil presents a monumental infrastructure challenge. The country’s major hydroelectric dams, such as Itaipu and Belo Monte, are often located in remote regions, far from the main consumption centers in the southeast and northeast. This necessitates a sprawling and complex network of transmission and distribution lines, spanning thousands of kilometers. The construction, maintenance, and operation of this grid are incredibly expensive, and these costs are a significant component of the final electricity tariff. The sheer scale of the country means that bringing power to every citizen is a costly endeavor, and these costs are ultimately socialized among all consumers, meaning a family in a Rio de Janeiro favela helps pay for the transmission lines that cross the Amazon.

Decoding the Conta de Luz: The Tariff Flag System and Hidden Costs

For the average Brazilian, the monthly electricity bill is a document filled with complex jargon, acronyms, and charges that are difficult to comprehend. At the heart of this complexity is the **Tariff Flag System (Sistema de Bandeiras Tarifárias)**, a mechanism created by the National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL) in 2015 to signal the real-time cost of energy generation. While intended to promote transparency and encourage conservation, it has become a primary driver of the financial burden on low-income households.

The system works through a simple color code, similar to a traffic light, which is applied to the electricity bills of most consumers:

- Green Flag (Bandeira Verde): This indicates favorable conditions for energy generation, typically when the hydroelectric reservoirs are full. Under the green flag, there is no additional charge on the bill.

- Yellow Flag (Bandeira Amarela): This signals less favorable conditions, requiring the activation of some thermal plants. A moderate surcharge is added to the bill for every 100 kilowatt-hours (kWh) consumed.

- Red Flag (Bandeira Vermelha): This is activated when generation costs are high, necessitating the extensive use of more expensive thermal power plants. The red flag has two levels, with Level 1 imposing a high surcharge and Level 2 imposing an even higher one.

- Water Scarcity Flag (Bandeira de Escassez Hídrica): A special, even more punitive flag created during the severe drought of 2021, imposing the highest surcharge of all.

The problem with this system is its regressive nature. The surcharge is a flat rate applied to consumption, meaning it affects low-income families disproportionately. For a wealthy household, a 25% increase in the electricity bill might be an annoyance. For a family living on the minimum wage, it can be catastrophic, forcing them to cut back on food or other necessities. This system, designed for transparency, has become a mechanism for transferring the hydrological risk of the entire country directly onto the shoulders of consumers, with the poorest suffering the most from the price shocks.

Beyond the Flags: A Sea of Taxes and Charges

The tariff flags are only one part of the story. The Brazilian electricity bill is laden with a host of federal, state, and municipal taxes, as well as sector-specific charges that can account for up to 50% of the final bill. The main culprits are:

- ICMS (Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços): A state-level value-added tax that is one of the heaviest taxes on electricity, with rates varying significantly from state to state.

- PIS/COFINS (Programa de Integração Social / Contribuição para o Financiamento da Seguridade Social): Federal taxes that are also levied on electricity consumption.

- CDE (Conta de Desenvolvimento Energético): A sector-wide charge used to fund a variety of public policies, including subsidies for renewable energy, rural electrification, and the social tariff itself. This creates a situation where the poor are, in effect, helping to subsidize their own discounts, along with a host of other programs.

- Public Lighting Contribution (CIP/COSIP): A municipal charge for the maintenance of public street lighting.

This complex and heavy tax burden turns the electricity bill into a major revenue-generating instrument for the government, but it does so in a way that is not progressive. Unlike income tax, which is based on the ability to pay, taxes on consumption hit the poor the hardest, as they spend a larger percentage of their income on essential goods and services like electricity.

The Social Electricity Tariff (TSEE): A Flawed Lifeline?

The Brazilian government’s primary policy tool to address energy poverty is the **Social Electricity Tariff (Tarifa Social de Energia Elétrica – TSEE)**. Created in 2002, the TSEE is a federal program that provides discounts on electricity bills for low-income families. To be eligible, a family must be registered in the **Cadastro Único (CadÚnico)**, the federal government’s unified registry for social programs, and meet certain income criteria (typically a monthly household income per capita of up to half the national minimum wage).

The program offers a progressive discount structure based on consumption levels. Historically, the discounts ranged from 10% to 65%, with the highest discount applied to the first 30 kWh of consumption. While the TSEE has been a crucial lifeline for millions, it has been criticized for several shortcomings:

- Limited Reach: For many years, enrollment was not automatic. Families had to be aware of the program and actively apply for it, leading to millions of eligible families being left out.

- Insufficient Discounts: Even with the discount, the high underlying cost of electricity meant that many families still struggled to pay their bills, especially when punitive tariff flags were in effect.

- Complex Structure: The tiered discount system was often confusing for beneficiaries to understand.

The “Luz do Povo” Reform: A New Era of Energy Justice?

In a major policy shift in 2025, the Brazilian government launched the **”Luz do Povo” (People’s Light)** program, which fundamentally reformed the TSEE. The most significant change was the introduction of a **full exemption** for eligible families with a monthly consumption of up to 80 kWh. This means that an estimated **60 million Brazilians** will no longer have to pay for their electricity consumption within this limit, being responsible only for taxes and public lighting fees [3].

This reform represents a monumental step towards alleviating energy poverty. By making enrollment automatic for all eligible families in the CadÚnico and providing a complete exemption for a basic level of consumption, the government has addressed two of the biggest flaws of the old system. The program also includes provisions for a 12% discount for a wider group of low-income families starting in 2026. The “Luz do Povo” program is a cornerstone of the government’s new energy policy, which aims to promote tariff justice and ensure that access to electricity is not just a reality, but an affordable one for all.

Systemic Challenges: Energy Theft and the Cost of Irregularity

Beyond the complex tariff structure and tax burden, the Brazilian electricity sector is plagued by a significant and costly problem: **energy theft**, colloquially known as *gatos*. In many low-income communities and favelas, informal and illegal connections to the power grid are rampant. This is not simply a matter of criminality; it is often a symptom of a deeper issue where the official service is either unaffordable, inaccessible, or both. These clandestine connections are not only dangerous, posing a risk of fires and accidents, but they also represent a massive financial drain on the system.

The cost of this stolen energy, estimated to be around **R$10 billion annually** [2], is not absorbed by the power companies. Instead, it is socialized and passed on to all paying customers in the form of higher tariffs. This creates a vicious cycle: as tariffs rise to cover the cost of theft, more people are pushed into energy poverty and are incentivized to resort to illegal connections, which in turn drives up the cost for everyone else. The paying poor are thus doubly penalized: they pay for their own electricity and also subsidize the losses from those who cannot or will not pay. Addressing this issue requires more than just policing; it demands a strategy of formalizing these communities, regularizing connections, and making the official service a viable and affordable option.

Market Liberalization and the Private Sector: A Double-Edged Sword

In recent years, Brazil has been undergoing a gradual process of liberalizing its electricity market, moving away from a state-dominated model towards one with greater private sector participation and consumer choice. This reform, which is set to expand significantly, will eventually allow residential consumers to choose their electricity provider, much like they choose a mobile phone operator. The goal is to foster competition, drive down prices, and improve service quality. However, for low-income consumers, this transition is a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, competition could lead to more innovative and affordable energy plans. On the other hand, there is a significant risk that private companies will focus on more profitable, high-consumption customers, leaving low-income and remote communities underserved. The “free market” may not have the incentives to cater to those who can only afford a basic level of consumption. This makes the role of the state and regulatory bodies like ANEEL even more critical. They must ensure that market liberalization does not come at the cost of universal service and that robust social safety nets, like the reformed TSEE, are in place to protect the most vulnerable. The success of this transition will depend on finding a delicate balance between market efficiency and social equity.

The Promise of Distributed Generation: Solar Power for the People?

Amidst the challenges, the rise of distributed renewable energy, particularly rooftop solar, offers a powerful potential solution to energy poverty. The cost of solar panels has plummeted in recent years, making small-scale generation more accessible than ever. For low-income communities, distributed solar offers a path to energy independence and a shield against the volatility of grid tariffs. A family with a solar panel on their roof is less exposed to the whims of the tariff flag system and the rising costs of grid electricity.

However, significant barriers remain. The upfront cost of installing a solar system, while decreasing, is still prohibitive for most low-income families. Access to credit and financing for these installations is limited. Furthermore, the regulatory framework for connecting these small systems to the grid can be complex. Several innovative programs, often led by NGOs and social enterprises, are working to overcome these hurdles. These initiatives are pioneering new models, such as community solar projects and micro-financing for solar installations in favelas. These projects not only provide cheaper, cleaner energy but also create local jobs and empower communities. Scaling up these solutions and integrating them into a national strategy for energy justice is one of the most promising pathways to a sustainable and equitable energy future for Brazil.

The Human Cost: Health, Education, and Social Impacts

The consequences of energy poverty extend far beyond the financial strain. The inability to afford adequate electricity has profound and lasting impacts on the health, education, and social well-being of millions of Brazilians. In the realm of health, the lack of reliable refrigeration means that families cannot safely store perishable foods, leading to a greater risk of foodborne illnesses and increased food waste. It also means that essential medicines that require refrigeration, such as insulin, cannot be stored at home, creating a life-threatening challenge for those with chronic illnesses. Furthermore, in a tropical country like Brazil, the inability to power a simple fan during increasingly frequent and intense heatwaves can lead to heat stress, dehydration, and other serious health complications, particularly for the elderly and young children.

The impact on education is equally devastating. Without adequate lighting, children cannot study or do their homework after sunset, putting them at a significant disadvantage compared to their peers from wealthier households. The digital divide is also exacerbated by energy poverty. Access to computers, the internet, and other digital learning tools is impossible without a reliable and affordable electricity supply, further limiting the educational opportunities and future prospects of children from low-income families. Energy poverty traps families in a cycle of disadvantage, where the lack of access to a basic service perpetuates and deepens existing social and economic inequalities.

The Gender Dimension of Energy Poverty

Energy poverty is not gender-neutral; it disproportionately affects women and girls. In many low-income Brazilian households, women are primarily responsible for domestic tasks such as cooking, cleaning, and caring for children and the elderly. The lack of affordable and reliable electricity makes these tasks more time-consuming, arduous, and dangerous. For example, without an electric or gas stove, women may be forced to cook with firewood or charcoal, exposing themselves and their children to harmful indoor air pollution. The lack of electricity also means that tasks must be completed during daylight hours, limiting women’s time for other activities, such as education, income-generating work, or rest.

Furthermore, the lack of public lighting in many low-income communities creates a significant safety risk for women and girls, who are more vulnerable to violence and harassment when walking home after dark. The fear of violence can restrict their mobility and limit their access to evening classes or employment opportunities. By the same token, access to electricity can be a powerful tool for women’s empowerment. It can free up their time, improve their health and safety, and open up new opportunities for education and economic participation. Any effective strategy to combat energy poverty must therefore include a strong gender perspective, ensuring that the specific needs and vulnerabilities of women and girls are addressed.

The Role of Technology and Innovation

While the challenges of energy poverty are immense, technology and innovation offer promising new pathways to a more equitable energy future. The digital revolution is transforming the electricity sector, enabling new business models and new ways of delivering energy services. Smart meters, for example, can provide consumers with real-time information about their energy consumption, helping them to save money and make more informed decisions. They can also enable more flexible and dynamic pricing, with lower tariffs during off-peak hours. For low-income consumers, this could mean the ability to run appliances like washing machines at night, when electricity is cheaper.

The rise of mobile technology and digital payments is also creating new opportunities. Pay-as-you-go (PAYG) solar systems, which allow consumers to pay for their energy in small, affordable installments using their mobile phones, have been highly successful in other parts of the world, particularly in Africa. These models overcome the barrier of the high upfront cost of solar and provide a flexible and accessible pathway to energy access. The development of more efficient and affordable energy storage solutions, such as batteries, will also be a game-changer, allowing households to store solar energy for use at night or during power outages. Harnessing the power of these and other technological innovations will be crucial in the fight against energy poverty in Brazil.

Impact on Small Businesses and Local Economies

The burden of high electricity costs is not limited to households; it also has a stifling effect on small businesses and local economies in low-income communities. For a small neighborhood grocery store, a bakery, or a salon, electricity is a major operational expense, second only to rent or labor costs. High and unpredictable electricity bills can erode already thin profit margins, making it difficult for these businesses to survive, let alone grow and create jobs. The inability to afford reliable power can also limit the types of businesses that can operate in these communities. For example, a business that relies on refrigeration, such as a small restaurant or a butcher shop, may be unviable due to the high cost of electricity.

This has a cascading effect on the local economy. When small businesses struggle, they are less able to provide jobs and services to the community. This can lead to a downward spiral of economic decline, where the lack of economic opportunity further entrenches poverty. Conversely, access to affordable and reliable electricity can be a powerful catalyst for local economic development. It can enable the creation of new businesses, the expansion of existing ones, and the creation of much-needed jobs. It can also improve the quality and variety of goods and services available to the community, improving the overall quality of life. Therefore, any strategy to address energy poverty must also consider the needs of small businesses and the role they play in building vibrant and resilient local economies.

The Political Economy of Energy in Brazil

To fully understand the persistence of energy poverty in Brazil, it is essential to look beyond the technical and economic aspects and consider the political economy of the sector. The Brazilian energy sector is a complex arena of competing interests, where powerful lobby groups, including large industrial consumers, agricultural producers, and the energy companies themselves, exert significant influence on policymaking. For decades, the tariff structure has been designed to favor large industrial consumers, who have historically benefited from subsidized electricity rates. This policy, which was intended to promote industrial development, has been criticized for placing an unfair burden on residential consumers, particularly the poor.

The CDE, the sector-wide charge that funds a variety of public policies, is a prime example of this dynamic. While it funds important social programs like the TSEE, it is also used to subsidize a wide range of other interests, including the coal industry and certain renewable energy projects. The result is a complex and opaque system of cross-subsidies, where it is often difficult to determine who is subsidizing whom. Many analysts argue that this system lacks transparency and is susceptible to capture by powerful interest groups. Reforming this system and making it more transparent and equitable is a major political challenge, as it would require taking on powerful vested interests. However, it is a crucial step towards building a fairer and more just energy system for all Brazilians.

The Way Forward: A Multi-pronged Approach to Energy Justice

Solving a problem as complex and deeply rooted as energy poverty in Brazil requires more than a single solution. It demands a coordinated, multi-pronged approach that addresses the issue from multiple angles simultaneously. The “Luz do Povo” program is a critical and foundational step, but it must be complemented by a broader suite of reforms and initiatives. The path to true energy justice involves a combination of bold policy changes, targeted investments, community engagement, and technological innovation.

A key pillar of this approach must be a fundamental **reform of the tariff structure**. The current system, with its volatile tariff flags and regressive surcharges, is no longer fit for purpose. Brazil needs to move towards a more stable and predictable pricing mechanism that shields consumers, particularly the most vulnerable, from the shocks of the wholesale market. This could involve the creation of a stabilization fund, financed by a broader and more progressive set of sources, to absorb the costs of droughts and other contingencies, rather than passing them directly on to consumers. It also requires a comprehensive **review of the tax and subsidy system**. The web of taxes and charges on the electricity bill needs to be untangled and reformed to make it more progressive and transparent. The CDE, in particular, must be redesigned to ensure that its costs are distributed fairly and that its benefits are targeted to those who need them most.

Another critical front is the fight against **inefficiency and irregularity**. The issue of energy theft cannot be solved through policing alone. It requires a long-term strategy of urban and social development, including the formalization of land tenure in favelas and the regularization of electricity connections. This must be accompanied by large-scale investments in **energy efficiency**. Programs to help low-income families replace old, inefficient appliances and to improve the insulation and design of their homes can lead to significant and lasting reductions in their energy consumption and bills. These programs are not just a social good; they are also a highly cost-effective way to reduce the overall demand for energy and the need for new power plants.

Finally, the transition to a more just energy system must be **inclusive and participatory**. The voices of low-income communities, women, and other marginalized groups must be at the center of the policymaking process. This means creating new channels for public participation and ensuring that regulatory bodies like ANEEL are not just accountable to the industry, but to all of Brazilian society. It also means empowering communities to become active participants in the energy transition, through the promotion of community-based renewable energy projects and other forms of local energy ownership. By bringing together the government, the private sector, civil society, and local communities in a shared effort, Brazil can build an energy system that is not only clean and efficient, but also truly just and equitable for all.

Conclusion: A Call to Action for a Brighter, Fairer Future

The story of electricity in Brazil is a tale of two countries, a narrative of immense potential coexisting with profound inequality. It is the story of a nation that powers its industries with clean, renewable energy, while millions of its citizens are plunged into darkness by the unaffordable cost of a single light bulb. This paradox is not an inevitability; it is the product of a series of historical choices, policy failures, and systemic injustices that can and must be corrected. The high cost of electricity for the poor is a brake on social development, a drain on public health, a barrier to education, and a fundamental violation of the right to a dignified life.

The recent reforms under the “Luz do Povo” program represent a historic and commendable turning point, a clear recognition from the state that access to a basic level of electricity is a fundamental human right, not a commodity to be bought and sold on the market. It is a crucial first step, but it cannot be the last. True energy justice requires a deeper and more comprehensive transformation of the entire sector. It demands a courageous and sustained effort to reform a tariff structure that is volatile and unfair; to build a tax and subsidy system that is progressive and transparent; to tackle the deep-rooted problems of inefficiency and irregularity; and to empower communities to become active participants in their own energy future.

This is a call to action for all sectors of Brazilian society. It is a call for policymakers to look beyond the technical complexities of the energy market and to see the human faces of energy poverty. It is a call for the private sector to embrace a new paradigm of corporate social responsibility, where profit is not pursued at the expense of social equity. It is a call for civil society to continue its vital work of advocacy, innovation, and community mobilization. And it is a call for all Brazilians to recognize that a country can only be truly developed when the benefits of its progress are shared by all.

Brazil has the resources, the technology, and the ingenuity to solve this paradox. By building a system that is not only green but also fair, the country can ensure that the light of progress and opportunity shines brightly in every home, regardless of income. The path is complex, the challenges are immense, but the goal is clear and non-negotiable: to transform electricity from a source of anxiety and debt into a true engine of social and economic development for all Brazilians. The time for a brighter, fairer future is now.

References

- Bezerra, P., et al. (2022). The multidimensionality of energy poverty in Brazil: A historical analysis. *Energy Policy*, 168, 113134.

- Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet (GEAPP) & PSR. (2025). *Pathways to Tariff Justice in the Brazilian Electricity Sector*.

- Secretaria de Comunicação Social. (2025). *Gratuidade na energia começa a valer para 60 milhões de brasileiros*.

The Future of Energy in Brazil: Challenges and Opportunities

Looking ahead, the future of energy in Brazil is at a crossroads, presenting both immense challenges and unprecedented opportunities. The country’s ability to navigate this complex landscape will determine whether it can finally resolve the paradox of being a green energy superpower with a population plagued by energy poverty. The decisions made in the coming years regarding investment, regulation, and social policy will have a profound and lasting impact on the lives of millions of Brazilians.

One of the most significant challenges on the horizon is the ongoing threat of climate change. As droughts become more frequent and severe, Brazil’s reliance on hydroelectric power will become increasingly precarious. This will necessitate a major push to diversify the country’s energy matrix, with a greater emphasis on other renewable sources such as wind, solar, and biomass. While Brazil has made significant strides in these areas, particularly in wind power, a much larger and more strategic investment is needed to build a truly resilient and climate-proof energy system. This transition will require not only new infrastructure but also a modernization of the grid to accommodate the intermittency of these new energy sources.

The expansion of the free energy market to all consumers, including residential ones, represents another major shift. While this liberalization holds the promise of greater competition and lower prices, it also carries significant risks. As discussed, there is a real danger that private companies will prioritize more affluent customers, leaving low-income and remote communities behind. The role of the regulator, ANEEL, will be more critical than ever in ensuring that the market works for everyone, not just the privileged few. This will require a new regulatory paradigm, one that is more proactive, more socially conscious, and more focused on consumer protection.

However, the future also holds immense promise. The technological revolution that is sweeping through the global energy sector offers a powerful toolkit for building a more equitable and sustainable system in Brazil. The falling cost of solar power and energy storage, combined with the rise of digital technologies like smart meters and mobile payments, is opening up new possibilities for decentralized, community-based energy solutions. These technologies have the potential to empower communities, create local jobs, and provide a pathway to energy independence for millions of Brazilians. The key will be to create a policy and regulatory environment that fosters innovation and ensures that the benefits of this technological revolution are shared by all.

Ultimately, the future of energy in Brazil will depend on the country’s ability to place social equity at the heart of its energy policy. It will require a recognition that access to affordable and reliable electricity is not just a technical or economic issue, but a fundamental question of social justice and human rights. It will demand a new social contract for the energy sector, one that is based on the principles of fairness, transparency, and inclusion. The path will not be easy, but with bold leadership, a clear vision, and a steadfast commitment to the well-being of its people, Brazil can build an energy future that is not only green and prosperous but also just and equitable for all.